The Quiet Resistance of Queer Remembrance

A visit to the forgotten gay graves of upstate New York

There’s something strange and electric about standing in front of a headstone and knowing something no one told you. My husband and I routinely visit cemeteries both for our fascination with the macabre, as well as our interest in history. They also make great places to walk in nature and explore new places.

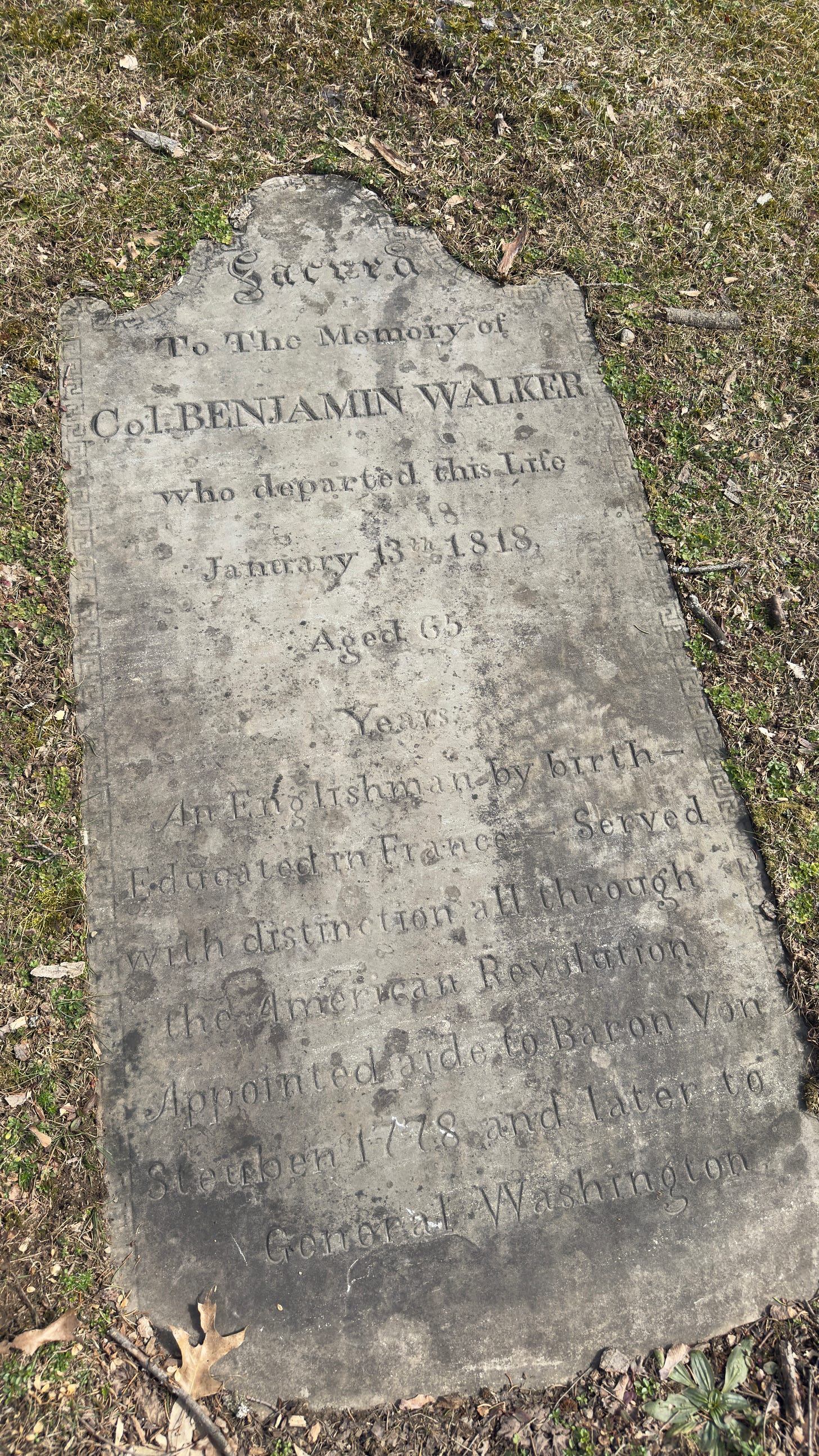

On a recent day trip, I stood before the grave of Benjamin Walker in Forest Hill Cemetery in Utica, New York. It’s a beautiful cemetery that is tree-lined, serene, and also vast and gothic. A place that asks you to slow down. But Walker’s grave isn’t listed in any queer tour guide or LGBTQ+ monument registry. To most, he’s just a figure from Revolutionary War history. To me—and to queer history—he’s something much more intimate: Baron von Steuben’s beloved companion.

Thirty miles away, von Steuben’s grave rests on a state park in Remsen. It is a stunning, simple tribute, put there by Walker. His monument is bolder, but his story—like so many queer stories—is still entombed in euphemism. Steuben, a Prussian military expert who helped train the Continental Army, never married and spent his life surrounded by young male aides. Upon his death, he “adopted” Walker and another young man, William North, to be his heirs. These chosen families—built in a time before legal or social recognition—were acts of survival and love. And yet, the official plaques don’t mention that. The monuments don’t say the word.

Which is why I go.

Visiting gay gravesites isn’t just a historical curiosity. It’s resistance. It’s reclamation. It’s queer archaeology. These places weren’t built to honor us. We were erased from the inscriptions. But we can read between the lines. We can piece the truth back together from letters, inheritance records, and the haunting, romantic proximity of one grave to another.

There is something deeply moving—almost mystical—about finding a queer life hidden in plain sight. Especially in public monuments designed to sanitize and simplify history. These aren’t just graves; they’re gateways. And once you start looking for them, they’re everywhere. Quietly waiting for someone to say: I know what you were. I see who you loved.

In a way, these visits are a kind of communion. Not with spirits, but with possibility. They whisper that queer people have always been here—writing, fighting, teaching, dreaming, and yes, loving. Even in the cracks of the official story.

This is the work I love most. The walking. The finding. The listening.

Because the past isn’t dead. It’s buried—and waiting.

Honoring the humanity in the history; I feel that deep connection to the past, and I am reminded that we write the future. Document, preserve and protect the

" facts" and also the TRUTH.

Thank you for a lovely article.

So interesting! I love old gravestones, and often they come with significant history attached. We need to know these stories from the past, especially when they risked being erased.