First, In Other News

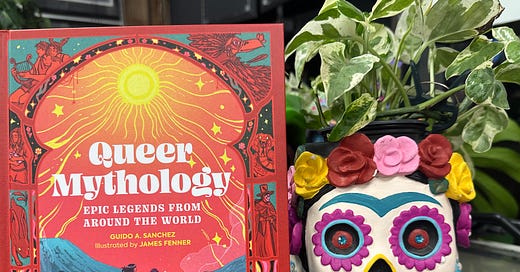

After a whirlwind launch month for Queer Mythology, October has come to a close, paving the way for a November brimming with more stories to share. I started the month already with a book signing at a local comic shop—a perfect blend of my worlds, myth and modern mythology—and look ahead to another book event on November 16th in Chatham, New York. These gatherings serve as celebrations of our timeless urge to connect through mythic heroes, be they gods or masked heroes.

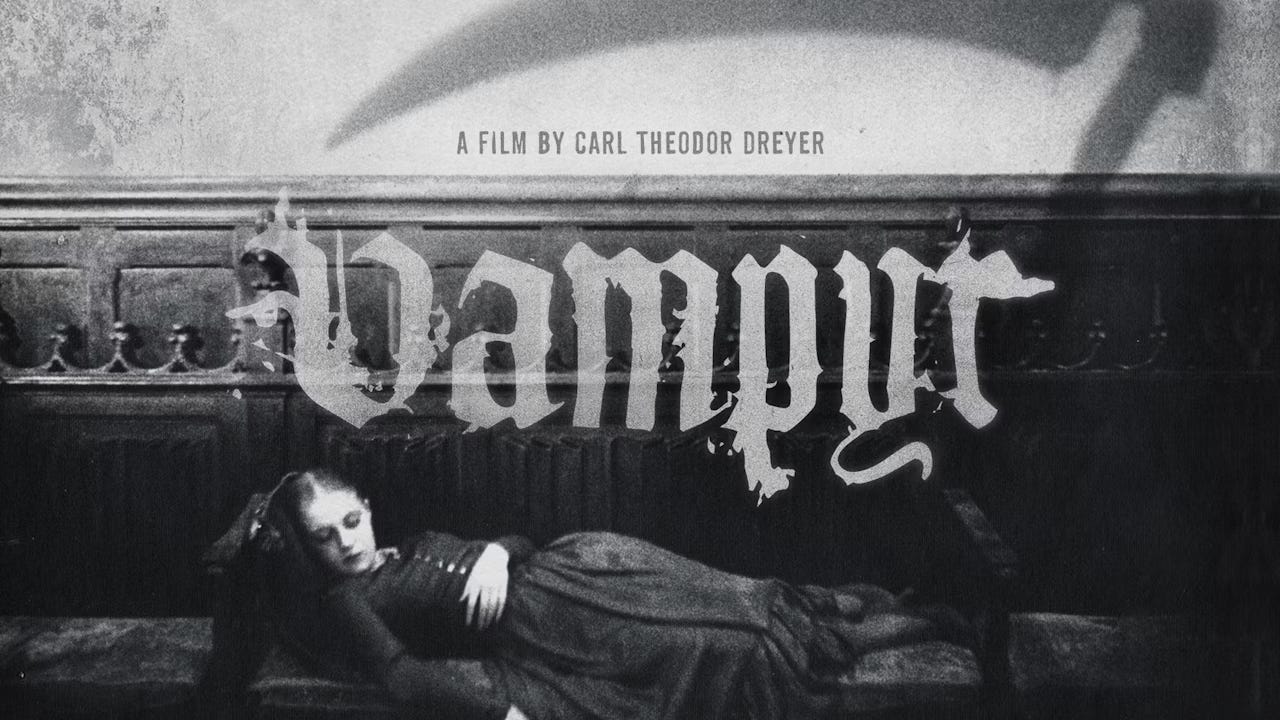

In this edition of The Substrate, we’re traveling back through the archives of Queer Immaterial, my podcast that brought to light the lives of icons living at the edges of history. This month's feature is a dive into horror with a lesser-known queer legend who found his way onto the silver screen in the haunting, ethereal film Vampyr. If you haven’t seen it, its eerie monochrome shades are as suited to November as a crackling fire and an early dusk. And Baron Niki—well, he’s as queer as they come, his influence quietly echoing through the layers of classic horror and fashion alike.

Each of these creative projects—past and present—is part of the journey to reveal the narratives often left in shadows, celebrating those who have always been part of the story, even when the world looked away.

The Baron & The Coffin

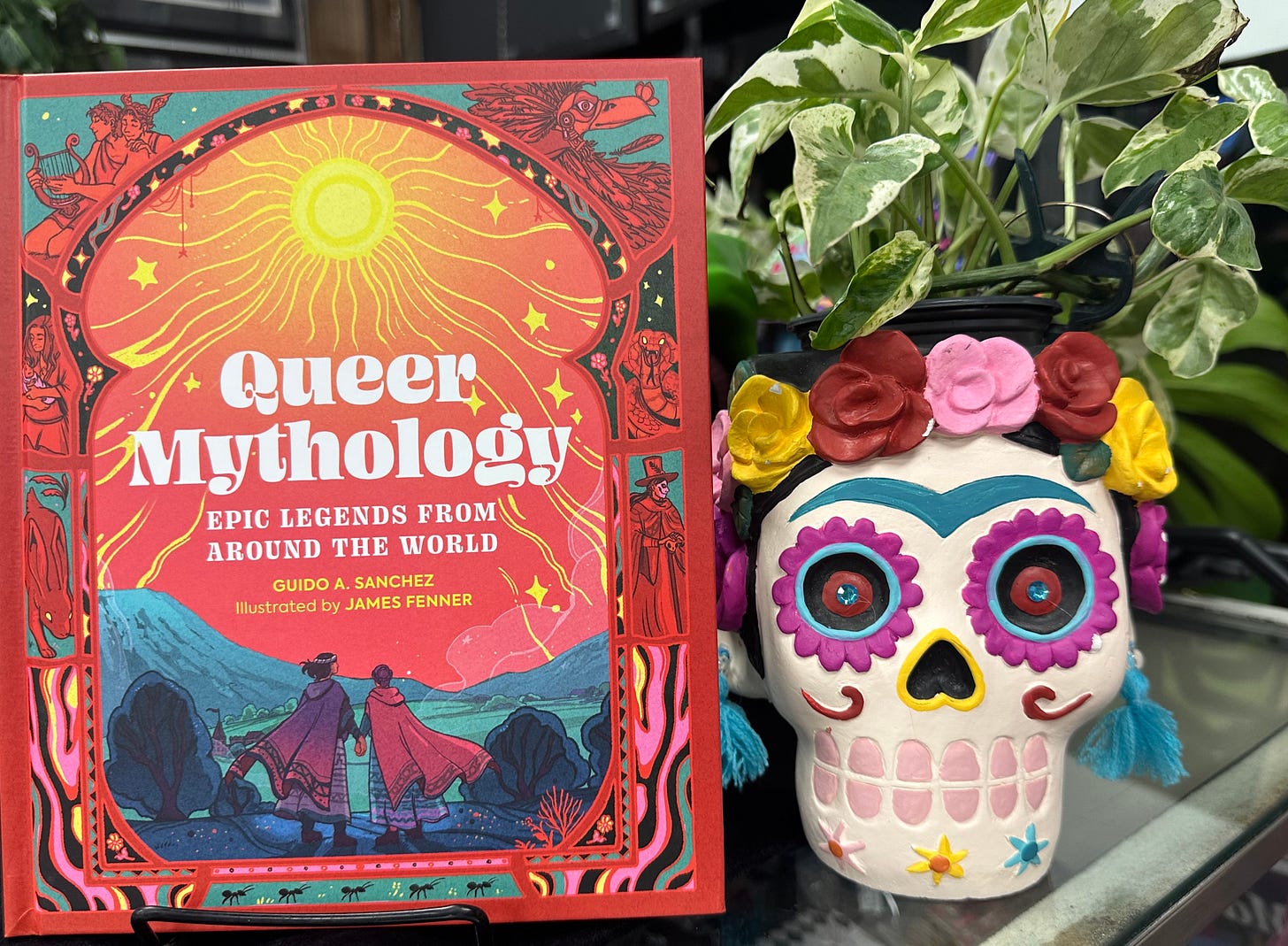

Baron Nicolas de Gunzburg, affectionately called "Niki" by those close to him, was born in 1904, his life touched by both privilege and a fiercely individual spirit. With a lineage tied to Russian nobility and banking powerhouses—his father Russian, his mother of Polish-Brazilian descent—Niki’s early years were steeped in both wealth and the weight of family legacy. By the 1920s and '30s, he had become a defining fixture of Parisian high society, where he was lauded as “one of the most civilized men in Paris.” Yet Niki’s elegance and refinement were coupled with a bold, avant-garde flair that made him both adored and talked-about.

In a city alive with artistic and intellectual fervor, Niki’s name became synonymous with opulent costume balls that enchanted and scandalized attendees. These weren’t just parties; they were spectacles of imagination, drawing in the leading artists, architects, and cultural icons of the time. Niki’s balls often revolved around themes of aristocracy, each guest dressed as royalty, or simply bathed in shades of white—a color that brought out the surreal grandeur of his gatherings. These events, styled with his own unique sense of fashion, were a blend of old-world nobility and modernist defiance, leaving an indelible mark on Paris’s social scene.

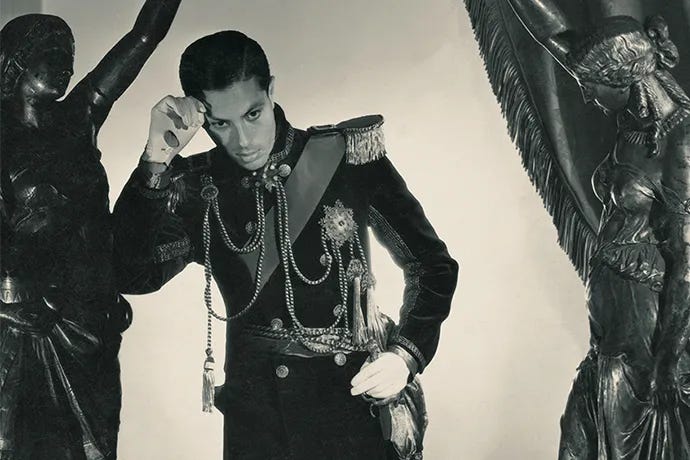

Beyond the allure of Paris’s most exclusive soirées, Niki’s impact on art and fashion began to emerge in subtler yet profound ways. His contributions were not limited to his iconic gatherings; they seeped into the fabric of culture itself, touching art, style, and even cinema. After a brief but memorable stint in film—acting and producing in a classic that still inspires our culture—Niki’s presence flickered across the silver screen, marking him as a unique figure who could bridge high society with horror. Though his acting career was short-lived, it left a mark as distinctive as the man himself.

Relocating to the United States, Niki made a single stage appearance in Los Angeles, but it was in his adopted home that his reputation as an arbiter of taste truly took root. He continued to host gatherings, drawing the cultural elite to events where every detail was curated with his unerring aesthetic sense. His parties in the States mirrored the avant-garde splendor of his Parisian past, but with a new edge—a melding of European sophistication with an American openness to reinvention.

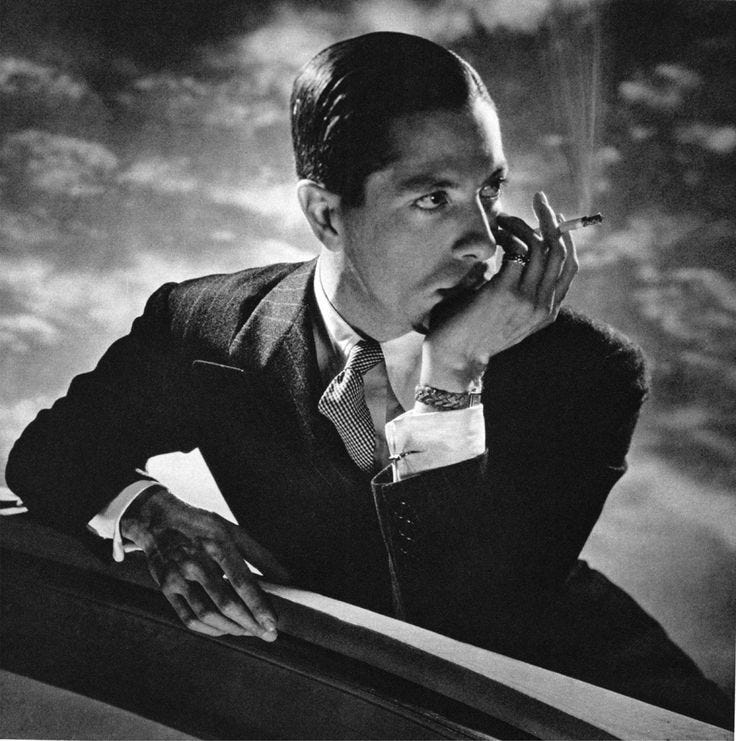

Counting Cole Porter among his closest friends, Niki inspired Porter to compose a score just for one of his parties, and Porter left him a considerable collection of art in his will. Perhaps this was, in part, repayment for Niki’s contributions to “You’re The Top,” the iconic Cole Porter song that Niki and a few friends helped write during a boating trip after an all-night party. Before formally beginning his career in fashion—where he would define style for decades to come—Niki continued hosting his legendary gatherings at his exquisite palace apartment in Manhattan, sometimes selling furniture or art pieces to fund his hosting. A Vogue writer once described Baron de Gunzburg as "a slender, attractive man with a really dry wit, a gift for mimicry, and a sharply developed taste for the simple but cultivated amenities of living."

The Baron began his editorial journey as a Fashion Editor at Harper’s Bazaar, eventually rising to Editor in Chief of Town & Country, and later serving as a Senior Editor at Vogue until the end of his career. In the 1940s, he lent his impeccable eye to decorate Christian Dior’s first New York location. Calvin Klein has often referred to him as his greatest mentor, remarking that Niki’s eye missed nothing. In Interview magazine, Klein shared, “He was truly the greatest inspiration of my life... he was my mentor, I was his protege. If you talk about a person with style and true elegance—maybe I’m being a snob, but I’ll tell you, there was no one like him. I used to think, boy, did he put me through hell sometimes, but boy, was I lucky. I was so lucky to have known him so well for so long.”

While at Harper’s Bazaar, he met and discovered Lauren Bacall in a restaurant, leading her into modeling and eventually to her first film role. Photographer Richard Avedon remembered him as the “only male fashion editor in the world” at that time. Always clad in black, Niki was celebrated for his sleek style, his keen eye, and his role in shaping many of the defining trends in both men’s and women’s fashion for decades to come.

Someone in Vogue’s art department once remarked, “Niki looked like a walking page of Vogue. He was the perfect signature of Vogue.” Diana Vreeland, the legendary Vogue editor, later admitted reluctantly that he taught her “everything, everything.” Known for his honesty, Niki’s forthrightness sometimes strained relationships with collaborators. On one occasion, when Vreeland asked him, “What is the name of that Seventh Avenue designer who hates me so?” Niki famously replied, “Legion.” He was eventually let go at age 70, a customary yet unwritten rule at Vogue, but continued to consult, playing a key role in the rise of Calvin Klein, as well as shaping the legacies of Dior, Balenciaga, and other iconic designers.

For several decades, Niki settled on a two-acre island he purchased in a New Jersey lake, naming it Hemlock Island after a single hemlock tree growing there. He shared this retreat with his partner, artist Paul Sherman. Kristina Aro, who served as housekeeper at Hemlock Island for years, remembers Baron de Gunzburg vividly: “You always learned a lot talking with him. He was a fascinating person. He treated everybody the same, whoever you were. And if he liked you, he always liked you, no matter what. But if he didn’t like you, it didn’t matter if you were a princess—he didn’t like you.”

Meanwhile, Reinaldo Herrera, husband of designer Carolina Herrera, dubbed Niki “the king of the gay fashion mafia.” His influence on style earned him recognition from Vanity Fair, which named him “one of the 20th century’s most powerful style arbiters” in 2014. Some described his iconic look as “like an undertaker,” while Noel Coward famously remarked that he dressed “like a nun” due to his constant preference for black or monotone colors.

Returning to those earlier days before his career in fashion, Baron de Gunzburg earned no fame as a movie actor and producer during his lifetime, yet he starred in and produced one of the most iconic and influential horror films. A true film enthusiast, Niki seemed destined for this connection; in 1931, he financed and starred in a film directed by the renowned Danish filmmaker Carl Theodor Dreyer, best known for his 1928 The Passion of Joan of Arc. Using the screen name Julian West, Niki helped bring Vampyr to life—a 1932 classic and Dreyer’s first sound film. The character of David Gray, protagonist of this German Expressionist-influenced, surrealist exploration of vampirism and horror noir, seems almost tailor-made for Niki; in fact, the original script even names the character Nicolas.

While it didn’t make Niki—or Julian West—a household name, Vampyr has garnered critical acclaim and, over the decades, secured its place as one of the classic early modern horror films, alongside Nosferatu and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. The film regularly appears on top horror film lists, and the celebrated critic Pauline Kael, writing in The New Yorker, noted, “Most vampire movies are so silly that this film by Carl Dreyer—a great vampire film—hardly belongs to the genre. Dreyer preys on our subconscious fears. Dread and obsession are the film’s substance, and its mood is evocative, dreamy, spectral. Death hovers over everyone.”

Reflecting with a local historian from his New Jersey home, Niki recounted the eerie scene in which David Gray lies in his coffin, eyes open, dreaming of his own death. The shot is both haunting and beautiful, with Dreyer’s techniques immersing the viewer inside the coffin alongside Niki. “In this movie,” Niki recalled, “I was supposed to lie in a coffin like this”—he placed his arms straight by his sides and stared ahead—“and during filming, one of those big movie lights, the bulbs just popped out, fell right into the coffin I was in, and exploded. And do you know, ever since that time, I have been simply terrified of light bulbs?”

It’s evident that Niki’s style and aesthetic sensibilities were integral to shaping both the character and the film he financed and produced—and that he was forever influenced by it. Niki’s New York apartment was famous not only for its art and gatherings but also for its memento mori collection of skulls, bones, and various detritus and ephemera related to death.

After his death, a 1970s clipping from The New York Times was found among his papers, in which a movie critic praised several early, overlooked masterpieces of silent horror—Vampyr in particular. In the margin of the clipping, in the Baron’s typically wry handwriting, was a note: “Fame at last!”

His funeral was small and intimate, attended by a select few, including fashion icons Bill Blass, Oscar de la Renta, and Calvin Klein. His maid recalled that the doctor shared the Baron’s last words: “I need my black boots.” She added, “Those black boots were his life. He wanted them always by his bedside.”